In the Center of the Semicircle, Part II

Today we’ll discuss how in recent decades some conductors have become superstars. As is the case with other sorts of superstar, so with high-powered globe-trotting conductors: they are still human, they are prone to do controversial things, and they end up taking a lot of heat for their presence in their particular musical kitchen.

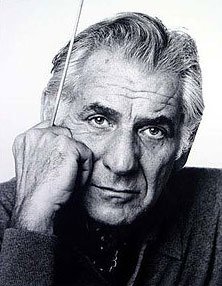

Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein like Stokowski before him, became known to mass audiences through the new 20th century media – beginning in 1954 he gave lectures on classical music to television cameras. He kept this up until his death in 1990. These lectures discussed (and provided aural illustrations of) Beethoven, jazz, conducting itself, musical comedy, and much else. Only recently have they been made into a DVD set.

Bernstein also became the maestro of the Young People’s Concerts, hosted by CBS.

But other achievements pale besides the fact that in 1958 Bernstein became conductor of the single most influential orchestra in the United States, the New York Philharmonic. It was a post he would hold for twelve years. Yehudi Menuhin, a renowned violinist and the founder of a prestigious school of music, has said that this was the perfect post for Bernstein.

Leonard Bernstein

He was “the embodiment, the crystallization of much of the life of New York, not only the Jewish expression by the various bases and the quality of the town itself.”

Politically, Bernstein was a man of the left and quite outspoken in this. The expression “radical chic” was invented for the sake of a satirical story about a party Bernstein threw for the Black Panthers. At Just Sheet Music, we take no side on political controversies, but we must note as a matter of history that his political activism, which did seem to too many like the recreational slumming of a high-brow, hurt him in the eyes of his public. He stepped down from the Philharmonic in the year of that notorious party.

That hardly meant an end to his conducting, or his influence. In 1972, Bernstein conducted several performances of the great Bizet opera, Carmen, at the Metropolitan Opera.

Throughout his career, Bernstein was the recipient of GRAMMY awards from The Recording Academy, beginning with a 1961 award for Best Recording for Children (for Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf). In 1967, he won Album of the Year, Classical, for a recording of Mahler’s Symphony No. 8. Bernstein had by then been for years the leading figure in bringing Mahler’s music to the attention of a mass audience. And in 1973, Bernstein won a Grammy for Best Opera Recording – for the aforesaid Carmen.

Seiji Ozawa

Seiji Ozawa was born of Japanese parents in occupied Manchuria in 1935. He didn’t see his/their homeland until after the war. Once there, he immediately began rigorous piano instruction under Noboru Toyomasu, focused on the works of J.S. Bach. But after an accident on a rugby field broke two of his fingers, he turned to composition, and to conducting, under the tutelage of Hideo Saito.

Yet Ozawa

Yet Ozawa

Ozawa was an assistant to Bernstein at the New York Philharmonic through the first half of the 1960s.

From 1965 to 1970, he held two quite demanding positions simultaneously: artistic director of the Ravinia Festival (an outdoor music festival sponsored by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra) and conductor of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. Much criticism has arisen from his alleged habit of spreading himself too thin, something that continued into the 70s and 80s.

For 25 years beginning in 1973, his base of operations was Boston, but again he drew irritated attention for his jet-setting ways.

A violinist said to a music critic: “He gets off the plane from Paris and starts to rehearse, and when he opens up the score of the symphony, he may not have looked at it since the last time he conducted it a year, maybe four years ago….we call it panic time when he’s around.”

Yet Ozawa obviously retained his admirers, and he won an Emmy in 1976 for a television series that aired on PBS, “Evening at Symphony.”

Since 2002, Ozawa has been the music director of the Vienna State Opera.

James Levine

James Levine(1943 – ) was the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 2001 to 2011. He succeeded

James Levine

Ozawa in that post. Even before doing that, Levine had in 2000 usurped Stokowski’s old role in the Disney remake of Fantasia. The newer version was, unsurprisingly, named Fantasia 2000.

Levine also has a long history with the New York Metropolitan Opera, directing its orchestra and chorus.

Before any of that, he was a figure of note in the Wagnerian world centered around Bayreuth, Germany. In a press conference at Bayreuth in 1989, Levine set off something of a storm, after conducting the orchestra for a performance of Parsifal produced by Götz Friedrich. Friedrich is known for his innovative stagings. Levine complained that with Parsifal, Friedrich was “going too far.”

Why did Levine go public with this thought? It is difficult to say. Heck, it was confusing to Friedrich, who said at the time, “he never communicated his reservations to me.”

It is well to remember in the face of such a story that the man standing in the center of the orchestral semicircle is never a god or even a demigod. Not even when he has been as built up by publicity machinery as each of these three men has been. Each is of course a dedicated and brilliant musical professional – each is human with faults and foibles.

Ton Koopman

Ton Koopman. I’d like to close this two-part discussion of conducting with a few words about with a few words about a contemporary conductor of note, Ton Koopman (1944 – ), a Dutchman who hasn’t received the publicity tsunami of a Bernstein, Ozawa or Levine, but who has become a central figure in the “authenticity” movement. This is a trend, of which I am personally an enthusiast, toward the creation of period music (most often, Baroque) in a manner appropriate to that time, informed by the state of the art in historical study. Thus, strivers for authenticity don’t bring in a 21st century style pianos for playing the works of Dietrich Buxtehude.

The instruments have to be authentic in construction, and in the mix that would be employed to make an ensemble, and of course any orchestra or other ensemble aiming at a historically informed performance will want a conductor attuned (excuse the pun) to that same end.

Koopman leads the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra. He generally conducts from the harpsichord, giving the orchestra members the needed visual clues with vigorous nodding of the head rather than with baton (or any potentially-fatal staff!) You may judge the results for yourself: