1812 in History and Music

September 7, 2012 is the bicentennial of the Battle of Borodino, one of the most dramatic events of the Napoleonic Wars, and a pivotal moment for both Russia’s music and its literature.

One the morning of that September 7th, in 1812, the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte and Czar Alexander I – the latter under the leadership of Field Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov – faced each other near where the rivers Kolocha and Voyna converged, between the villages of Novoe and Utitsa. There had been actions in the vicinity in each of the two proceeding days, but they seem in hindsight not battles at all, mere preliminaries, fights that helped move each army into the respective positions that would prove so devastating in the clash of the 7th.

‘Listen to this beautiful Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture while reading this article’

From Tolstoy to Woody Allen

As Tolstoy emphasized in War and Peace, the Russian position by the start of that fatal day was a defensive crouch behind unfinished entrenchments, and since its commanders were ignorant of the positions of the French, they ended up fighting virtually the entire French army with just their own left flank.

As Tolstoy emphasized in War and Peace, the Russian position by the start of that fatal day was a defensive crouch behind unfinished entrenchments, and since its commanders were ignorant of the positions of the French, they ended up fighting virtually the entire French army with just their own left flank.

In Woody Allen’s 1975 comedy, Love and Death, Woody’s timid pacifist, Boris Grushenko, is seen wandering across the battlefield terrified. He hides inside the nearest empty space he can find, which turns out to be the mouth of a cannon. He faints, and the voiceover tells us, “When I came to I realized I had made a terrible mistake.” He is shot out of the cannon, and lands on a group of French generals. They surrender and he is an “inadvertent hero.”

The actual battle was, as you might expect, much less amusing.

I won’t give blow-by-blow, but will skip to the upshot. The Russian defense of their position was impossibly valiant and stubborn. Nonetheless, at the end of that horrible day, [roughly 33,000 killed or wounded on the French side, 44,000 on the Russian side] the Russian army was in retreat and the French stood in possession of the battlefield. The victorious army stood there licking its wounds, utterly unprepared for immediate pursuit.

I won’t give blow-by-blow, but will skip to the upshot. The Russian defense of their position was impossibly valiant and stubborn. Nonetheless, at the end of that horrible day, [roughly 33,000 killed or wounded on the French side, 44,000 on the Russian side] the Russian army was in retreat and the French stood in possession of the battlefield. The victorious army stood there licking its wounds, utterly unprepared for immediate pursuit.

There was no other position between Borodino and Moscow where another set-piece battle could be waged. The result of this one ensured the French would take Moscow. But of course with the occupation of Moscow and the onset of winter their real troubles would begin.

Fittingly, there would be a battle in 1941 on the same real estate, between the German and Soviet armies, known to historians as the “Battle of Borodino Field.” Despite the advance in the science of armaments between 1812 and 1941, the latter battle was less deadly than its precursor had been.

The Overture

That earlier battle was the grim material with which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky had to work in order to create what he was committed to creating in 1880, a piece to be performed for the 25th anniversary of the coronation of Czar Alexander II the following year. He completed the work in only six weeks.

That earlier battle was the grim material with which Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky had to work in order to create what he was committed to creating in 1880, a piece to be performed for the 25th anniversary of the coronation of Czar Alexander II the following year. He completed the work in only six weeks.

On a superficial level, his composition follows the order of the campaign, with Borodino in its center. Thus, the overture begins quietly, as a hymn. The French have invaded, and the Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church has asked that his flock pray for divine intervention.

Over the coming weeks, the French advanced steadily, and there was some skirmishing with Russian forces. We hear both the French national anthem and our composer’s take on Russian folk music intertwining during this period in the Overture.

Then the composer depicts vividly for us the clash at Borodino with its climactic musical chiaroscuro, cannons and all.

The French enter Moscow and all seems to be lost. You can listen to the final four minutes here, a selection that opens as God is about to enter history in answer to Russia’s prayers. The music diminishes to a whisper: then the quiet hymn with which the piece began re-occurs, fully orchestrated this time. At points along the way we hear the musical equivalent of whistling winter winds, representing the French abandonment of the city and the start of their disastrous march westward.

Finally, all is the ringing of triumphant bells in the liberated city, and a brass fanfare representing a great national victory. In indoor performances the part of a brass band is often played by an organ.

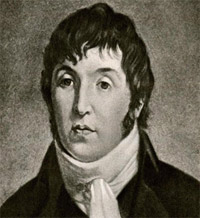

Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle

The theme used repeatedly to represent the French army in Tchaikovsky’s Overture is a snippet from La Marseillaise. That seems unquestionably appropriate but is in fact an anachronism. Napoleon had banned that revolutionary tune in 1805; he wanted to bank the fires of revolutionary ardor for the sake of stability and for his own peace of mind. It didn’t become the national anthem again until Bonaparte was long gone, and certainly wouldn’t have been used by any musicians with the French troops on their Russian campaign in 1812.

The theme used repeatedly to represent the French army in Tchaikovsky’s Overture is a snippet from La Marseillaise. That seems unquestionably appropriate but is in fact an anachronism. Napoleon had banned that revolutionary tune in 1805; he wanted to bank the fires of revolutionary ardor for the sake of stability and for his own peace of mind. It didn’t become the national anthem again until Bonaparte was long gone, and certainly wouldn’t have been used by any musicians with the French troops on their Russian campaign in 1812.

Still, it is itself a fascinating composition and worth further notice here. It was written and composed in 1792 by one Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle at Strasbourg, where he was quartered as part of the “Army of the Rhine.”

The lyrics are fittingly militaristic:

Aux armes citoyens

Formez vos bataillons

Marchons, marchons

Qu’un sang impur

Abreuve nos sillons

Or, on English, if I understand this: “To arms citizens, form your battalions, march, march, Let their impure blood water our fields.”

And we must in this context mention a certain scene in Casablanca.

And we must in this context mention a certain scene in Casablanca.

But to return to Tchaikovsky, and the way in which he settled his accounts with Napoleon’s ghost … what can we say about this, as a piece of music? It is not generally seen as one of its composer’s greatest works. Few lovers of his work would place the Overture ahead of the music from any of his three great ballets, for example, or ahead of that of the opera Eugene Onegin.

Still, it is too often written down as “bombastic,” by those who want to think themselves superior. Yes, it is gimmicky, but it has some wonderful effects. That opening hymn, intended to represent Orthodox religious fervor, is accomplished with an economy of means, a sextet of strings, two violas and four cellos. A bit later, the strings start to alternate with woodwinds, a neat instrumental simulation of choral antiphony, as the composer’s sympathetic biographer, David Brown, has observed.

Let us close with an Austin Texas based rock/classical fusion band, The Invincible Czars, who have released a version in their own distinctive style recently in celebration of the bicentennial of the events depicted.