Fishing in the Depths of Benjamin Britten

This year is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Benjamin Britten, a great English composer and conductor who created several outstanding operas: Peter Grimes (1945), Billy Budd (1951), and The Turn of the Screw (1954) among them. [The Queen had made him a peer in 1976, and Britten died of congestive heart failure later that year.]

Benjamin Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976)

We’ll take a few minutes today to praise Lord Britten, by means of admiring descriptions of each of the three operas just named.

Two of the three have a maritime theme, the third goes fishing in psychological depths instead.

Peter Grimes

Peter Grimes drew inspiration from a collection of George Crabbe poems, The Borough, published in 1810. In one of the poems in that collection, Peter Grimes, a fisherman by trade, mistreats his apprentices, and [or consequently?] each dies while in his charge. After each of the first two deaths Grimes is acquitted – after all, the townspeople reason, fishing is a dangerous craft, the unskilled youngsters involved sometimes die, etc.

After the third time, the borough’s officials get tough with him; he is prohibited from buying any further indentured servants. “Hire thee a freeman,” says the mayor.

Thereafter he is shunned by the towns’ people. This shunning and his own guilt collude to drive Peter mad.

Thereafter he is shunned by the towns’ people. This shunning and his own guilt collude to drive Peter mad.

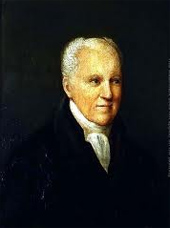

Grimes himself becomes a much more sympathetic figure in Britten’s treatment, with the assistance of his librettist Montague Slater, than he had been in Crabbe’s. Crabbe (portrayed left) describes Grimes as a “savage master” who discovered, upon buying the first of his doomed indentured boys, that “he’d now the power he ever loved to show/ A feeling being subject to his blow.”

But in the hands of Britten and Slater, Grimes becomes a misfit loner deserving of sympathy. It is the town, he sings, that ought to be ashamed, “Selling me new apprentices,/ Children taught to be ashamed/Of the legend on their faces – ‘You’ve been sold to Peter Grimes!’” Softening the character becomes easier by virtue of the reduction of the number of his victims: ‘only’ two apprentices die in the opera, rather than the three of the poem.

But in the hands of Britten and Slater, Grimes becomes a misfit loner deserving of sympathy. It is the town, he sings, that ought to be ashamed, “Selling me new apprentices,/ Children taught to be ashamed/Of the legend on their faces – ‘You’ve been sold to Peter Grimes!’” Softening the character becomes easier by virtue of the reduction of the number of his victims: ‘only’ two apprentices die in the opera, rather than the three of the poem.

We see a more important change when we come to the manner of Grimes’ death. He doesn’t go mad as a result of anything as mild as a general shunning. Rather, he is pursued by an angry mob, singing “Him who despises us we’ll destroy.” Click that song title for a YouTube clip of 23 minutes from the opera. If you’re impatient, skip forward to about 19:30, when the people of the borough have persuaded themselves that Grimes has done something awful to the second apprentice. See how the crowd is both angry and joyous in equal measure – joyous in its very unity – and how all this is musically expressed.

The choice of this material for an opera was Britten’s, a decision made a year before he requested Slater’s help. The bare plot might seem on first thought a slender thread on which to hang a drama. Yet on second thought the suspicions the town directs against Peter stand for other sorts of suspicion, whether directed at innocent or at not-to-innocent targets. The opera becomes a meditation on the psychology of crowds. That has been the gist of commentaries like this.

Billy Budd

Billy Budd was a novella by the superb American writer Herman Melville, one left unpublished at his death in 1891. Since its first publication in 1924, it has become a central work in the canon of great 19th century novels.

Billy Budd was a novella by the superb American writer Herman Melville, one left unpublished at his death in 1891. Since its first publication in 1924, it has become a central work in the canon of great 19th century novels.

Britten’s opera from this work boasts a libretto by E.M. Forster and Eric Crozier.

That libretto includes a priceless bit of self-referential dialogue, as the Master at Arms ‘welcomes’ the newly-impressed members of his crew. Click here for the ten-minute scene that includes this:

“Can you read?

“No, but I can sing.

“Never mind the singing.”

This opera received a posthumous compositional assist from Giuseppe Verdi. According to an anecdote from Mervyn Cooke’s biography of Britten, Peter Pears (a tenor who was Britten’s long-time lover) sent Britten a score of Verdi’s La Traviata while he, Britten, was in the midst of a blockage on this project. In a letter to Pears, Britten thanked him for the gift and added, “I’m in a bit of a muddle over Billy & not ready to start on him again yet. Anyhow one learns so much from Verdi so B.B. will be a better opera for your present, I’ve no doubt!”

This opera received a posthumous compositional assist from Giuseppe Verdi. According to an anecdote from Mervyn Cooke’s biography of Britten, Peter Pears (a tenor who was Britten’s long-time lover) sent Britten a score of Verdi’s La Traviata while he, Britten, was in the midst of a blockage on this project. In a letter to Pears, Britten thanked him for the gift and added, “I’m in a bit of a muddle over Billy & not ready to start on him again yet. Anyhow one learns so much from Verdi so B.B. will be a better opera for your present, I’ve no doubt!”

Pears played Captain Vere in the opera’s first run.

Turn of the Screw

Turn of the Screw has nearly as lofty a literary pedigree as Billy Budd. Turn was a ghost story written by Henry James, originally published in 1898, with a story that is on its face the struggle for the souls of two children, a young boy and girl named, respectively, Miles and Flora. The combatants in this struggle are: their governess (who is not given any name in the story) who is surely working for the side of good; and two ghosts, one of them that of a former governess, Miss Jessel, who seeks possession of the waifs.

That, as I say, is the struggle on its face, because there have been many readings of the story that have held that this is not really what is going on, that the ghosts don’t exist outside of the deluded mind of the current governess, and that she herself is the real danger to the children she thinks she is protecting. The ambiguity is surely part of the reason Rebecca West once called this novella “the best ghost story in the world.”

That, as I say, is the struggle on its face, because there have been many readings of the story that have held that this is not really what is going on, that the ghosts don’t exist outside of the deluded mind of the current governess, and that she herself is the real danger to the children she thinks she is protecting. The ambiguity is surely part of the reason Rebecca West once called this novella “the best ghost story in the world.”

Britten worked with librettist Myfanwy Piper in preparing this work for the operatic stage. This was the first Britten/Myfanwy collaboration, though it would not be the last. They worked together in another Jamesian text, Owen Wingrave, years later, and on an opera based on a work by Thomas Mann, Death in Venice, after that.

Here is one interpretation of their Turn of the Screw. For the 1982 movie, director Petr Weigl introduced a long wordless opening sequence that shows Jessel and her lover, Peter Quint, when they were still alive and already a corrupting influence on the children. At about 6:30 in that clip, there’s an erotically charged close-up of Jessel biting into an apple in the estate’s garden, and of course sharing the fruit with the children. [Things get even worse when she’s dead.]

That Britten’s work, like James’, is subject to a variety of interpretations makes life interesting for producers and directors.

Final Thoughts

Speaking of the subtle and psychological side of ghost stories … Britten’s Turn might be in a sense a precursor of the great Stanley Kubrik movie, The Shining. You can see that this story, too, was much enhanced by the musical element. Original music for its soundtrack was provided by Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind, but the most effective spooky music in the soundtrack comes from Krzyztof Penderecki, his De Natura Sonoris No. 2.

I think Penderecki would have gotten along well with Henry James.

But let us return to Britten. Here is our farewell to a versatile genius. This clip will give you the music that accompanied the Governess’ first reactions to her new abode, as the screws begin turning: