Three Recent, and Very Different, Books on Music

Healing at the Speed of Sound

By Don Campbell and Alex Doman

Hudson Street Press, New York City, 2011.

288 pages, $25.95

This is the latest in a recent spate of books treating of the psychological, indeed the neurological and embryological, origins of our appreciation for and our human ability to create music.

Such books have been very popular ever since Don Campbell came out with The Mozart Effect in 1997. That book argued for the beneficial effects of exposing infants to classical music, including although of course not exclusively that of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. This book is Campbell’s latest in the same line, with the assistance of Alex Doman. Doman is an entrepreneur, founder of Advanced Brain Technologies, which provides tools for music based therapies.

Campbell and Doman ask you to think about the first sound you ever heard. It was the beating of your mother’s heart, which your developing nervous system began to process as a central fact in its uterine world sometime in the second trimester of development. Your appreciation of steady rhythmic sounds – the backbone of musical appreciation – began there.

Soon enough, you discriminated other sounds, like the gurgling noise of the digestive system, and “the comforting vibration of your mother’s voice resonating throughout her body and yours.” Indeed, you eventually began to pick up on the existence of a world outside your mother’s body. Campbell and Doman quote a Penn State neuroscientist who has said “there is a lot of information in that filtered and muted sound stream.”

The music that makes it through the filter is stored away and continues to exercise an influence on post-natal life. Research indicates, for example, that infants respond to the theme songs of the television shows that their mothers watched most often during pregnancy. One natural conclusion is that mothers who are interested in musically gifted children might want to surround themselves with fine music during gestation. (And, by the way, what’s the downside? What harm could it do, even if speculation about the benefits is overblown?)

Another natural conclusion is that music has helped to shape who we are in a deep way, so that everyone – even the most tone-deaf among us – is entitled to say, along with Kiki Dee, “I’ve got the music in me.”

Indeed, let’s pause to enjoy that one on YouTube.

The Castrato and His Wife

The Castrato and His Wife

By Helen Berry

Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2011.

288 pages, $29.95

This book is certainly a change of pace from that one. It takes us from timeless truths to some very contingent historical facts. On September 8, 1773, William Long Kingsman married the daughter of the Maunsell family, Dorothea. Both families had musical associations, so it probably seemed especially appropriate that the wedding took place in the Parish Church of St George, Hanover Square, in London. This was the church where George Frideric Handel had been the appointed organist half a century before. It was, writes historian Helen Berry in this new book, still in the 1770s “the venue for many of the most prestigious concerts of sacred music in the capital….”

But why should this particular marriage in that church be deemed important for us, in the early 21st century? Because the bride was already married, and she would have to seek an annulment of her earlier marriage (something she didn’t get around to doing for another year and a half) in order to throw retrospective legitimacy over this one. And because the estranged husband she had left for Kingsman was … Giusto Ferdinando Tenducci, a renowned international opera performer, and a castrato.

Tenducci was sufficiently renowned to have been immortalized by the above painting, by no less a figure than Thomas Gainsborough.

The fact that Tenducci was a castrato, and thus in the language of the legal documents of the day “totally incapable of the Act of Procreation,” would prove adequate grounds for the annulment, although there was nothing straightforward about that. Tenducci acknowledged being a eunuch, and it was in his line of work something of a selling point. Back in the 1660s, eunuchs as singers had been new for London musical aficionados and the diarist Samuel Pepys had written, disapprovingly, that many in his social circles “dote of the Eunuchs.”

Pepys, in a famous portrait (below), has turned to his right. Gainsborough, as above, is looking left. When you put the two together, it appears the two men are ignoring each other, each in favor of the document in his hand.

Pepys

By the 1770s though, the novelty of eunuchs had worn off. Tenducci was a member of a class of singers who had been an established part of the musical scene for a long time. At any rate, there was no secret about his anatomy.

Still, the law required proof, not mere notoriety. The Kingsman family seems to have gone to a good deal of trouble to hunt down witnesses, not just to Tenducci in naked adult moments but to the operation itself, which had been performed in his boyhood, in 1748, by a physician who had died in the meantime.

The story of the Tenducci-Maunsell marriage, and its annulment to legitimate the Kingsman-Maunsell wedding, gives Berry, and she gives us, a visa into both the sexual/social mores of the European Enlightenment and its musical scene.

Steve Jobs

By Walter Isaacson

By Walter Isaacson

Simon & Schuster, New York City, 2011.

656 pages, $35.

For our last selection we will stay within the realm of the contingent, but the history involved is quite recent. Steve Jobs, co-founder and for long periods the central figure at Apple, died last year, just as Simon & Schuster was readying this book for the stores.

Jobs’ life and work had an incalculable impact on the music industry. Some even claimed that he saved it from itself. Thus, Isaacson’s book, which devotes a good deal of careful attention to the musical side of the Jobs/Apple story, deserves its part in our triptych.

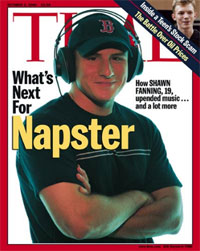

Remember Napster in its heyday? Shawn Fanning and his buddies became fodder for the cover of major news magazines by helping music lovers share MP3 files over the internet, cutting the music industry out of the loop. Metallica discovered that a demo of a song they hadn’t released, “I Disappear” was circulating in this way in early 2000, and that triggered the litigation, and eventually the court order, that shut down this early incarnation of Napster.

Remember Napster in its heyday? Shawn Fanning and his buddies became fodder for the cover of major news magazines by helping music lovers share MP3 files over the internet, cutting the music industry out of the loop. Metallica discovered that a demo of a song they hadn’t released, “I Disappear” was circulating in this way in early 2000, and that triggered the litigation, and eventually the court order, that shut down this early incarnation of Napster.

Still, it had been a scary trip for the music moguls, there were other similar services out there, and Jobs persuaded the moguls (or enough of them) that unless they did something drastic, their day was done. That something drastic turned out to be: industry cooperation with iTunes and the iPod.

Isaacson tells us that Jobs knew he could have effectively encouraged and enabled pirating, offering his iPad (without of course saying so) as a new tool. But he didn’t want to go that route because he believed creative people should have property rights and a profit incentive for further creation.

He quotes from an interview Jobs gave Esquire, “So we said, let’s create a legal alternative to this. Everybody wins. The artists win. Apple wins. And the user wins, because he gets a better service and doesn’t have to be a thief.”

And we will let that be our happy ending, too. These books are each suitable for any music lover’s shelf, or eReader.

And we can all enjoy Metallica.