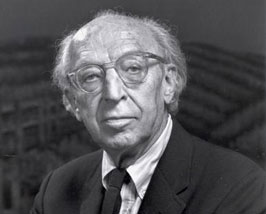

An Appreciation of Aaron Copland

Tags: Aaron Copland, ballet, composer, musical, orchestral

In 1938, the American frontier got its very own ballet.

After a long period of what seems in hindsight apprentice work, Aaron Copland achieved Master status in the American musical canon in 1938, with a ballet commissioned by Lincoln Kirstein, and named for the western gun-slinger William H. Bonney, or Billy the Kid.

In the world of orchestral music, “Billy the Kid” was America’s “Declaration of Independence.” Copland, composing for the choreography of Eugene Loring, broke away from European models as surely as Jefferson had in politics, or as Whitman had in poetry. Though he drew upon the classical ballet and orchestral traditions, he also used actual cowboy and folk music, and his score seems at time to evoke the spaciousness of the prairie.

In broadest terms, Billy himself is a symbol for America, and for the taming of various frontiers in our history, as well as the transition from chaotic, nomadic, and pastoral ways of life to ways more lawful, settled, and industrial. Billy has to be killed by Pat Garrett as one America has to give way to another.

Though Copland’s fame as a composer grew in the coming years, he wouldn’t be confined to that role. He remained, also, a conductor. His most definitive biographer, Howard Pollack, has written that in leading an orchestra Copland “cultivated a long lyrical line and leisurely tempos that fluctuated slightly,” and says that this puts him in the tradition of Europe’s romantic composer-conductors such as Sergei Koussevitzky and Paul Hindemith.

The Second World War came to America in December 1941, and Eugene Goosens, the conductor of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, responded by asking a lot of American composers to write “fanfares” that would be performed at concerts. Eighteen composers responded, and the result was a range of now-mostly-forgotten work such as Bernard Wagenaar’s “Fanfare for Airmen” and Paul Creston’s “Fanfare for Paratroopers.” But Copland’s response to Goosens’ request has not been forgotten: “A Fanfare for the Common Man” remains in the orchestral repertoire. Its longevity has even received an assist from Emerson Lake and Palmer.

There is a global dimension, too, to Copland’s next remarkable ballet, Rodeo. “Rodeo” was commissioned by the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, which asked Agnes de Mille to choreograph and to choose the composer at will. She had seen “Billy the Kid” and approached Copland. He was at first reluctant – the requests seemed too much like asking him to compose a variation on that earlier work.

But DeMille brought him around. What she had in mind was, in its underlying plot, quite different from “Billy the Kid.” It was a romance employing unnamed allegorical characters. The protagonist, Cowgirl, fancies the Head Wrangler, but he seems rather more attracted to the more feminine Rancher’s Daughter than to our protagonist. Cowgirl (danced by Agnes DeMille herself when Rodeo premiered at the Met in October 1942) gets her way at the Hoe Down, though.

Copland’s best-known and best-loved work is Appalachian Spring. This, too, was first composed to score a ballet, although it is almost invariably performed in our own day as an orchestral suite. When Copland was working on the score for this work, it did not yet have that name. His working title for it was “Ballet for Martha,” – a reference of course to the choreographer Martha Graham.

Graham proved a very different sort of collaborator. Both of his earlier choreographers, Loring and DeMille, had given Copland detailed outlines of what they wanted, minute-by-minute and sometimes even dance-move by dance-move. Graham, on the other hand, reversed the direction of cause and effect. She wanted to develop moves for her dancers that would fit his music, rather than demanding from him music that would complement the predetermined moves.

Indeed, what guidance Graham did give Copland about the dancing turned out to be misleading, as she kept changing it. Copland first watched the ballet in rehearsal only a few days before opening night in the autumn of 1944. He later said that he was surprised to find “music composed for one kind of action had been used to accompany something else….But that kind of decision is the choreographer’s, and it doesn’t bother me a bit, especially when it works.”

Copland famously included within his score the Shaker tune “Simple Gifts”, which itself dates back to the 1840s, and constitutes a setting – the time, place, and mood – for the whole ballet. What was crucial, in Copland’s own words, was that “it had to do with the pioneer American spirit, with youth and spring, with optimism and hope.”

As for the title of the ballet, “Appalachian Spring,” it comes from a poem, appropriately titled The Dance, by Hart Crane. In context, the word “spring” in that poem refers not to the time of year but to the sources of a stream, the “watery webs of upper flows,” as Crane put it.

Despite many achievements, including some that have gone unmentioned here, Copland’s body of work contains one notable disappointment. In 1954, Copland tried his hand at opera, composing “The Tender Land.” He wrote it as a tragic look at the demise of the family farm in America, thinking it would be broadcast on NBC. Though that television network passed on it in the end, it was staged by the New York City Opera in April 1954. It closed after only two performances.

Even many of Copland’s admirers have agreed with the judgment of the market. Musicologist Elise Kuhl Kirk, for example, has complained that the opera presents “a landscape with painted figurines rather than a drama of vivid, moving human beings.”

Copland’s influence lives on – indeed, it is amplified with the passage of time. The next generation of America composers included Leonard Bernstein, an avowed disciple of Copland. Indeed, Bernstein’s music at one point in his development sounded so much like Copland that Copland himself warned him that he’d have to develop a distinctive sound.

West Side Story, a Broadway musical that premiered at the Winter Garden Theatre on Broadway in September 1957, brought together two artists of Copland’s lineage. Bernstein of course composed the music, and Jerome Robbins – who had directed The Tender Land three years before – did the choreography. Parts of West Side Story could almost have been another Copland ballet.

Indeed, we may fittingly end with a YouTube video that illustrates that point: